When, in 1983, your humble servant was granted the inestimable privilege of meeting Sir Georg Solti, he asked the fiery and irreplaceable Maestro what musical event—e.g: excluding concerts and opera performances—had left the strongest impression on him. Without hesitation, he declared: « My meeting with Richard Strauss at his villa in Garmisch-Partenkirchen!«

Now, among the many preserved houses formerly belonging to composers across Europe, this particular residence had still been missing from our list. Not that we hadn’t already located it: during one of our previous Bavarian trips, we caught a glimpse of it in 1995 from beyond its gate. But at the time, no « open sesame » allowed us entry, as we were told the place was strictly off limits to visitors. Thirty years later, thanks to a new trip—and the prospect of writing an article for Résonances Lyriques once unattainable dream had at last taken shape…

However, we should clarify that even today, the interior of the villa remains closed to the general public. Access conditions remain restrictive, limited to professionals and researchers, and requires prior application—properly justified—submitted to the Richard Strauss Institute.

This magnificent villa was built between 1907 and 1908 to serve as the summer residence of the Munich-born composer. Strauss proved extremely meticulous in his dealings with Emanuel von Seidl (1856–1919), a Bavarian architect associated with historicism but open to Jugendstil [Art Nouveau] influences, and a contemporary of painter Franz von Stuck. On numerous occasions, Strauss intervened directly in the development of the plans, precisely stating his requirements. The most striking example is the corner tower, which unmistakably identifies this elegant three-level residence located at 42 Zoeppritzstraße.

It should be noted that the creation and subsequent international success of Salome made possible the construction of a pleasure residence commensurate with the social success brought about by artistic triumphs, both in opera and in symphonic poems—two major pillars of an incomparable body of work.

Under the guidance of Dr. Dominik Šedivý, accompanied by two Austrian colleagues and an Australian fellow, our captivating visit lasted two and a half hours, during which time we hardly noticed the passing of time.

The grand entrance hall surprises with its abundance of hunting trophies and animal mounts1. However, it should be emphasized that Richard Strauss himself greatly disliked hunting—unlike his son Franz (1898–1980), who practiced it extensively—regarding it as « an organized massacre of animals. »

The visit continues with a key room: the dining room2. Strauss always sat in the same place at the table, cherishing the ritual of meals.

A deeply monarchist man, firmly rooted in the 19th century, he staunchly upheld traditions—not out of routine, but because they supported the continuity of a European civilization to which he remained profoundly attached. One senses his presence in every corner of the house, alongside that of his muse, naturally: his wife Pauline3.

A musician of exceptional technical skill, she significantly influenced the evolution of Strauss’s style after their marriage. When composing, Richard liked to feel her nearby, and he enjoyed the comings and goings, even the bustle, of the children, whose games and laughter brought him joy and inspiration. For him, composition and warm family life remained deeply intertwined.

Artworks and souvenirs of various kinds abound on the walls, furniture, and shelves, including framed glass cases containing giant exotic butterflies, mostly brought back from South America. Moreover, numerous objects of sacred folk craftsmanship represent Pauline’s main contribution to these astonishing collections. Though himself agnostic and rather anticlerical, Richard Strauss remained a passionate admirer of religious art.

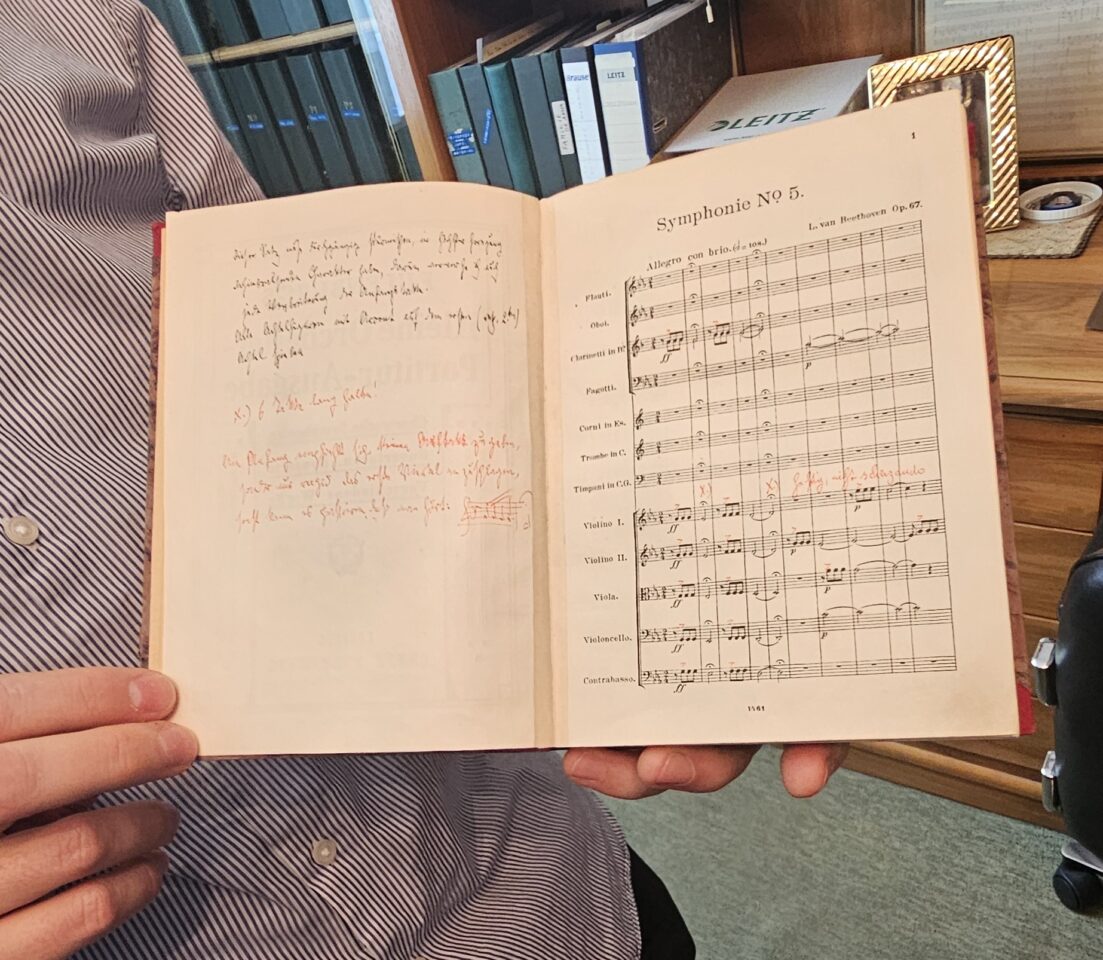

We then proceed to the spacious study, designed by the architect according to his meticulous instructions, including the furnishings. It houses a comfortable library, preserved by the family after the Master’s death, just as the entire home has been maintained. All the books contain his scattered handwritten annotations. Together, they form a vast catalogue reflecting his immense culture, ranging from ancient authors to his contemporaries4.

For instance, we are told that he read the complete literary legacy of Goethe no fewer than three times in his life. His entire creative output greatly benefited from the readings and enduring passions he maintained for the visual arts, mythology, history, geography, and psychoanalysis (the absolute antithesis of today’s majority of opera directors, who dare elevate ignorance, mediocrity, and vulgarity to the status of fine art).

A small anecdote shared by our host along the way: contrary to such encyclopedic culture, the composer of Elektra adored sweets, candies, or confections, depending on his mood. In later years, to preserve his failing health, Pauline allowed him… a maximum of three to five chocolates per day…

While famous paintings (by El Greco, Crivelli, Rubens, etc.) shine on the walls, our eyes are immediately drawn to a large canvas depicting a deeply concentrated Strauss conducting Così fan tutte at the Wiener Staatsoper. Seeing it in situ, rather than in its (rare) reproductions, deeply moves us.

Yet we are even more awestruck when we lower our gaze to the desk of the creator of Der Rosenkavalier. An indefatigable worker, he used it for hours on end. The leather surface even bears the imprint left by the constant pressure from his free hand, kept motionless while, he inscribed either musical notes or words with the other.

At this very spot, Metamorphosen and the Oboe Concerto were the final scores composed by the great genius at the twilight of a richly lived life. Nearby stands a grand Ibach piano, custom-made and sumptuously marquetried.

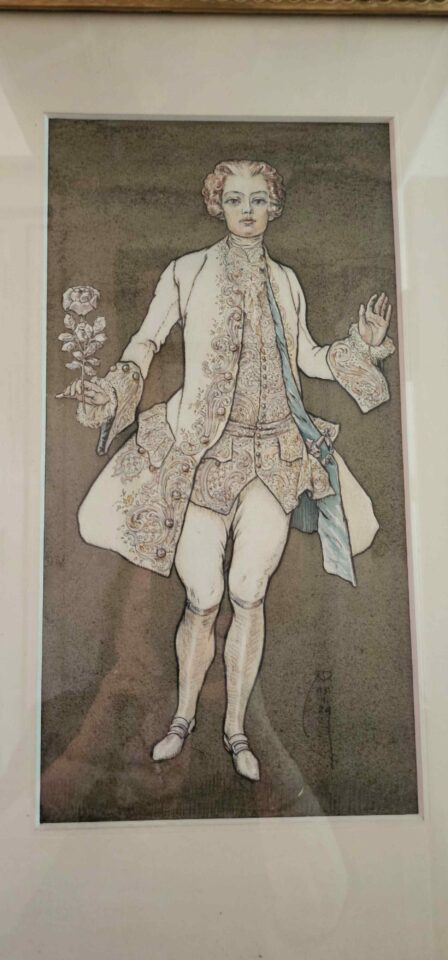

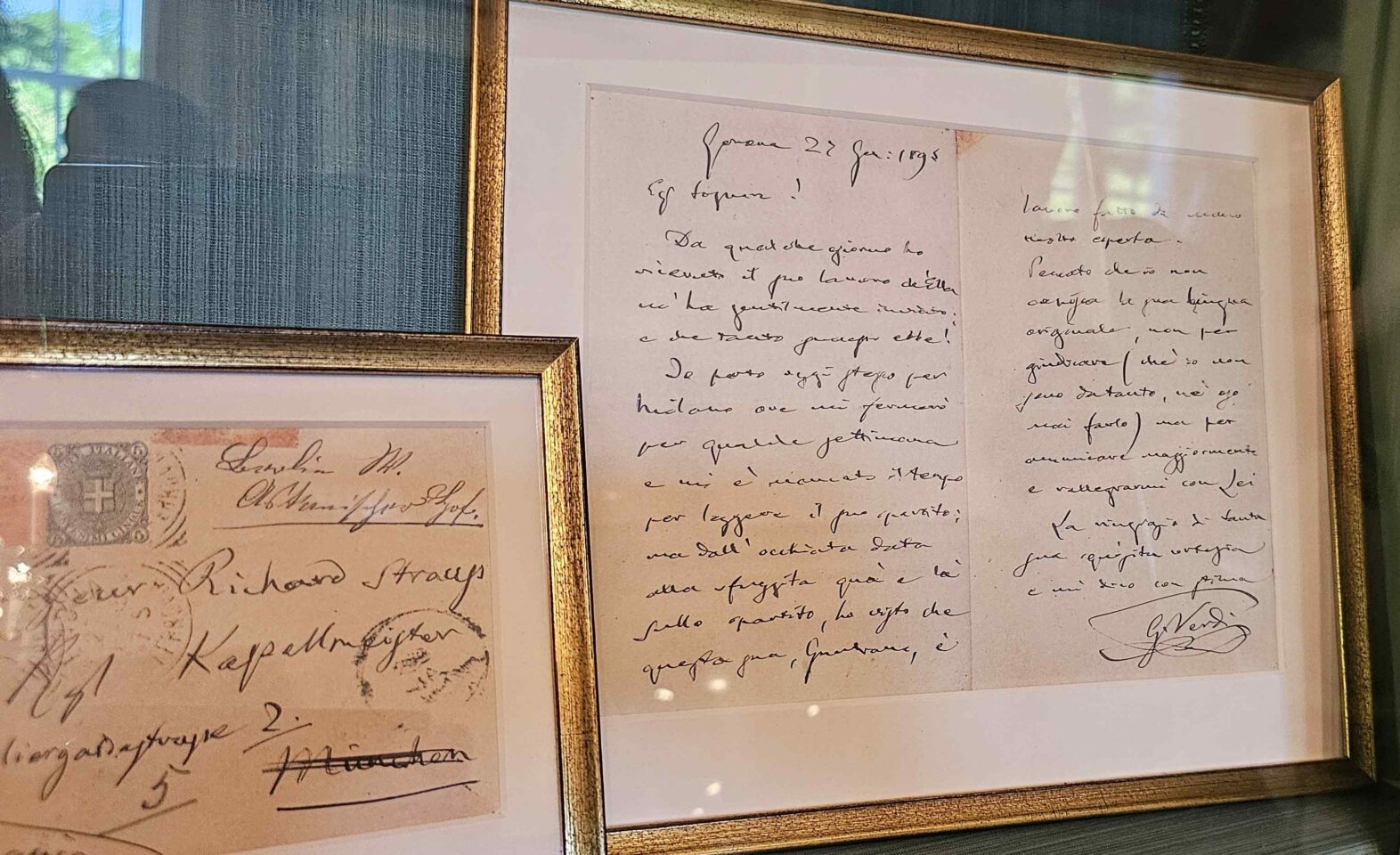

The adjoining room prolongs the sense of awe that has taken hold of the visitor, displaying numerous letters collected from other composers: Mozart, Verdi, Wagner… (among others!), piously arranged beneath the gaze of a Greek statue of a female deity and an elegant Meissen porcelain equestrian figurine of Auguste Le Fort.

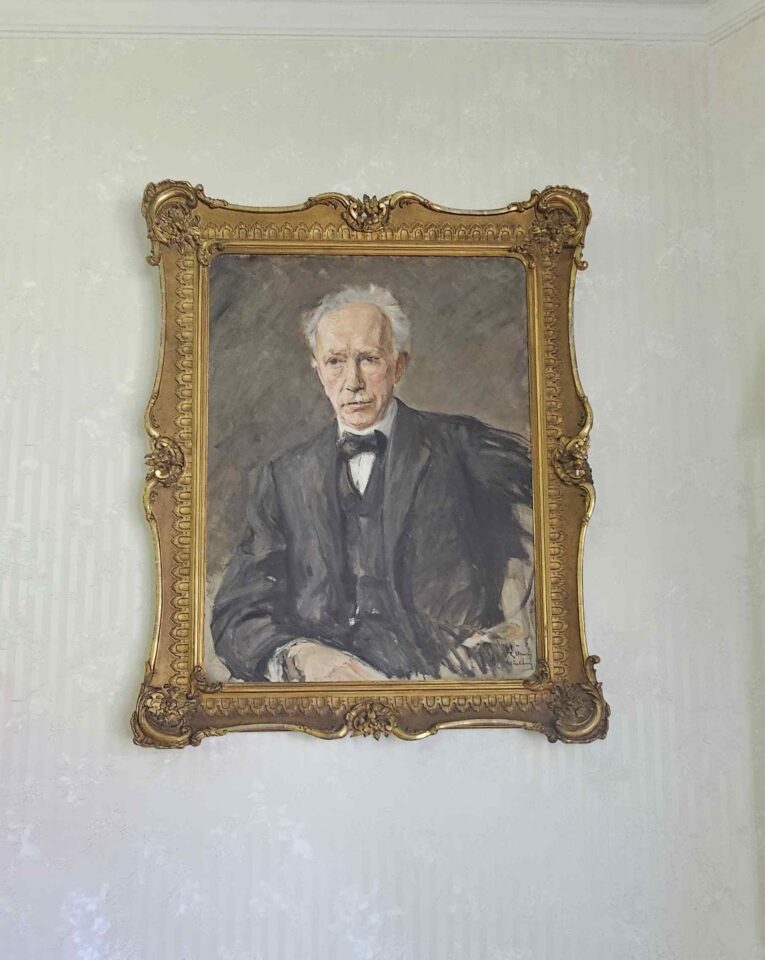

We proceed to the grand salon, added in 1924, where several rarely reproduced official portraits of the composer of Arabella hang—including, in our opinion, one of the most magnificent, painted by Max Liebermann—alongside more intimate photographs, including one showing Pauline around the time of their marriage. Equally touching are the display cases filled with crystals, among them several splendid pieces from the Murano glassworks.

On the first floor, emotion reaches its peak in the room where Strauss passed away5. It serves as a memorial, with his death mask resting on a Jugendstil-style marquetry piano. Though confined to bed from July 1949, his mind remained lucid until he drew his final breath on Thursday, 8 September a date still marked on the perpetual calendar atop his desk.

Passing next into the charming breakfast room, we enter a large study room, a relatively recent addition, rich with an abundance of original documents, before reaching the music library, overflowing with biographical works and scores.

This space aptly recalls the primary mission of the site: to stand as a reference center for research. Among the treasures offered to our contemplation are the Master’s personal poetry notebooks, as well as several conducting batons, including one used in the 1890s, followed by a precious ebony-and-ivory « honor baton » received in 1944.

From the windows, one glimpses the gardener’s house—now home to Constantin Strauss, the great-grandson who, among five great-grandchildren, lives closest to the memory of his illustrious forebear, that magician of sound whose presence seemed to linger with us throughout this unforgettable journey through time.

We extend our heartfelt thanks to Herr Doktor Dominik Šedivý, our erudite and graciously courteous guide, for these rare and exceptional moments tinged with something of the marvellous.

Patrick Favre-Tissot-Bonvoisin

Traduction : Cécile Beaubié

1 In the hunting sense of the term.

2Let us note that for the creation of Intermezzo—an opera fundamentally autobiographical—in Dresden in 1924, the stage design reproduced this dining room almost exactly.

3 Born Pauline de Ahna, a professional opera singer and daughter of a general officer in the Royal Bavarian Army.

4 Polyglot, he also read Greek and Latin in the original, with a particular fondness for the Iliad… Nevertheless, he tried to pass on this passion for Homer to his grandson Christian, who told him… he preferred Jules Verne.

5On this occasion, we learn that Pauline and Richard were sleeping in separate bedrooms, ‘for the sake of a healthy lifestyle’.